Remembering a Groundbreaking Cancer Researcher

April 29, 2022

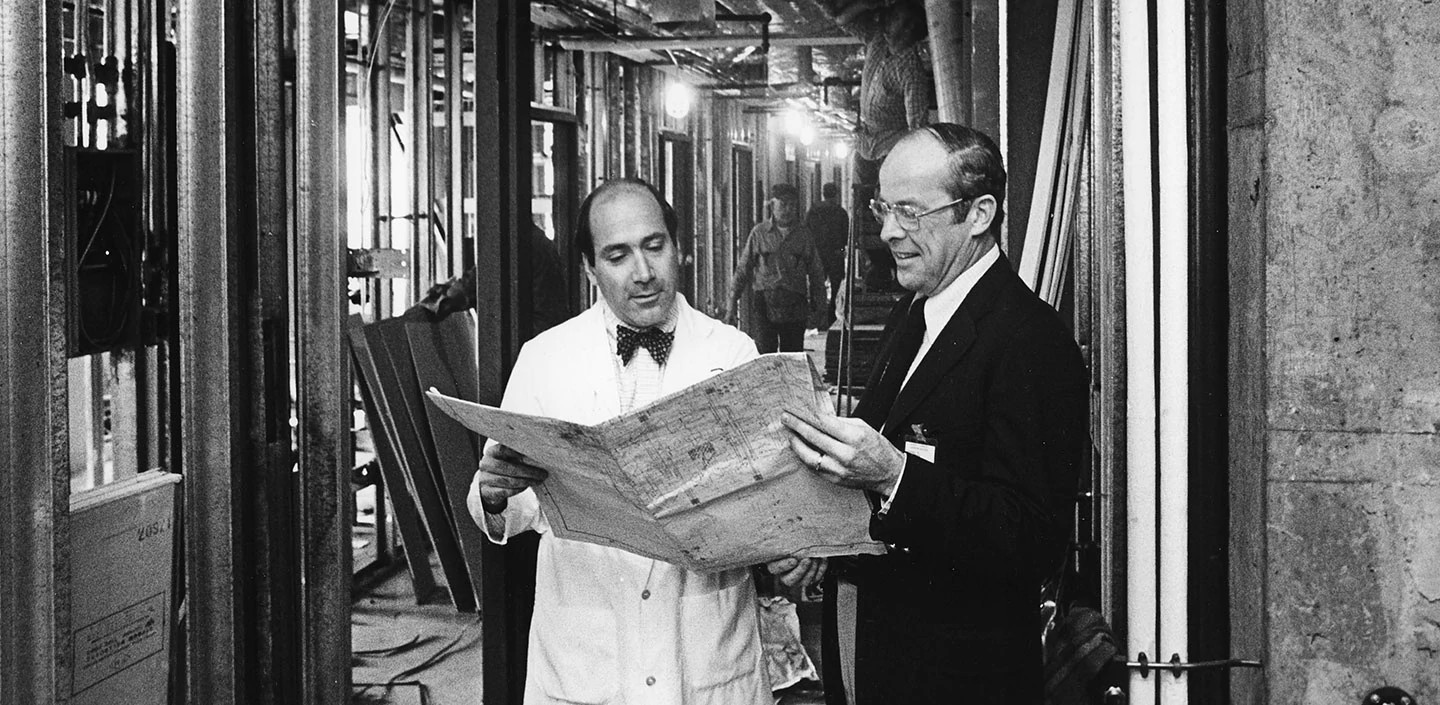

David Livingston, MD (left), reviewing Jimmy Fund Building renovation plans with longtime Dana-Farber staff member Thomas McNamara.

David Livingston, MD, presenting at an NCI visit to Dana-Farber.

David Livingston, MD (left), Emil Frei III, MD (middle), and Lee Nadler, MD.

David Livingston, MD (left), Daniel Vasella, CEO of Novartis (middle), and Edward J. Benz Jr., MD (right), at the Sidney Farber Awards.

David Livingston, MD (right), helped guide the career of Sarah Hill, MD, PhD (left, at her MD/PhD graduation), who now leads her own Dana-Farber laboratory.

David Livingston, MD (right), speaking at a reception honoring William Kaelin Jr., MD, for winning the 2016 Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research.

Fostering Collaboration

Livingston was born in Cambridge, Mass., and educated at Exeter, Harvard University, and Tufts University School of Medicine, after which he completed training in internal medicine at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. His postdoctoral training was at the National Institutes of Health and HMS, before being recruited to Dana-Farber.

After the isolation of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 in 1994, there was uncertainty about where in the cell the BRCA1 protein carried out its functions. "David's group was one of the first to make monoclonal antibodies that answered the question of where the BRCA1 protein was localized, and the Livingston group determined in a landmark paper that it is located in the cell's nucleus," Hill explains. As a result, "you could finally ask: What does BRCA1 do? The antibodies used in those experiments were so critical, and people are still using them constantly."

Brown says that Livingston's work identifying the role of BRCA1/2 in DNA damage repair "was the fundamental discovery that resulted in the development of PARP inhibitors that are used to treat breast and ovarian cancers from people with BRCA1/2 mutations."

Judy Garber, MD, MPH, was one of the principal investigators of the OlympiA trial that recently reported a disease-free survival benefit for BRCA1/2-mutant breast cancer treated with the PARP inhibitor olaparib, says Brown. Garber, who leads Dana-Farber's Cancer Genetics and Prevention program, wasn't one of Livingston's trainees, but she was a very close collaborator over the years and worked to translate Livingston's work to the clinic.

After Livingston's death, many leading scientific journals published obituaries or appreciations penned by his colleagues and former trainees. Kaelin, for example, wrote a long, personal essay in the journal Cell. "David methodically sculpted me into a scientist (and talked me out of quitting at least six times while I was in his laboratory, when the work seemed too frustrating and hard), and his mentorship and advocacy for me continued almost until the very day that he died," wrote Kaelin. "My eventually winning the Nobel Prize says more about David than it does about me."

Invariably, the memorial essays described Livingston's groundbreaking efforts to foster collaboration among scientists, from his larger institutional accomplishments to the informal retreats at the Livingston family farm for the purpose of open sharing of unpublished research findings — and always accompanied by memorable meals and stories served up by the prominent scientists at the retreats.

"David was instrumental in bringing people together in the fight against cancer, and he led the effort to establish the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC)," wrote Brown and DeCaprio in an obituary in Nature. "In doing so, he brought together a prestigious yet somewhat reluctant group of leaders and investigators from seven Harvard institutions and served as its deputy director from 1999 to 2019."

Brown and DeCaprio also noted that Livingston was instrumental in forming an academic-industry partnership between Dana-Farber and Sandoz (now Novartis) in the early 1990s that has continued ever since. "David's vision played a key role in the development of several Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted cancer therapies," they said.

More recently, Livingston worked with Tyler Jacks, PhD, at MIT to develop the Bridge Project, a collaboration between DF/HCC and the Koch Institute for Integrative Research at MIT. Bridging the Charles River geographically and different disciplines metaphorically, it brings together cancer researchers and bioengineers from MIT with clinical oncologists from Harvard's hospital consortium to address pressing problems in cancer care.

Sarah Hill, who says she talked to Livingston the Friday before the weekend on which he died, said she is still deeply saddened by his passing, but continues to be inspired by his zeal for research and ambition to improve treatments for breast and ovarian cancer — and possibly to prevent them.

"He used to say to us, there are women in the hospital here who are so sick and losing their hair — we have to do something better for this disease," says Hill. "I think he would have found ways to detect cancers early and how to prevent them. Making sure David's legacy is honored is a huge thing for everyone who worked with him."

David Livingston made it possible for us to dream big about the future of Dana-Farber, because that was how he saw it, and his unflagging enthusiasm and love for the institution and everyone in it lifted our hearts and spirits every day.

That is also true for Dana-Farber President and CEO Laurie H. Glimcher, MD, who, although she was not one his trainees, expressed the feelings of many when she said, "We have lost not just a source of comfort but a source of inspiration. David Livingston made it possible for us to dream big about the future of Dana-Farber, because that was how he saw it, and his unflagging enthusiasm and love for the institution and everyone in it lifted our hearts and spirits every day. Surely, there is no better way to honor his memory than to do what he spent his life doing."