How Dana-Farber Is Spearheading New Strategies to Correct Historical Trends and Disparities in Cancer Care and Prevention

January 5, 2024

Breast Cancer

Ovarian Cancer

Gynecologic Cancer

Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity

Survivorship

Cancer Genetics and Prevention

By Robert Levy

Over the past 40 years, survival rates have risen for nearly every form of breast and gynecologic cancer, but not every patient has benefited equally.

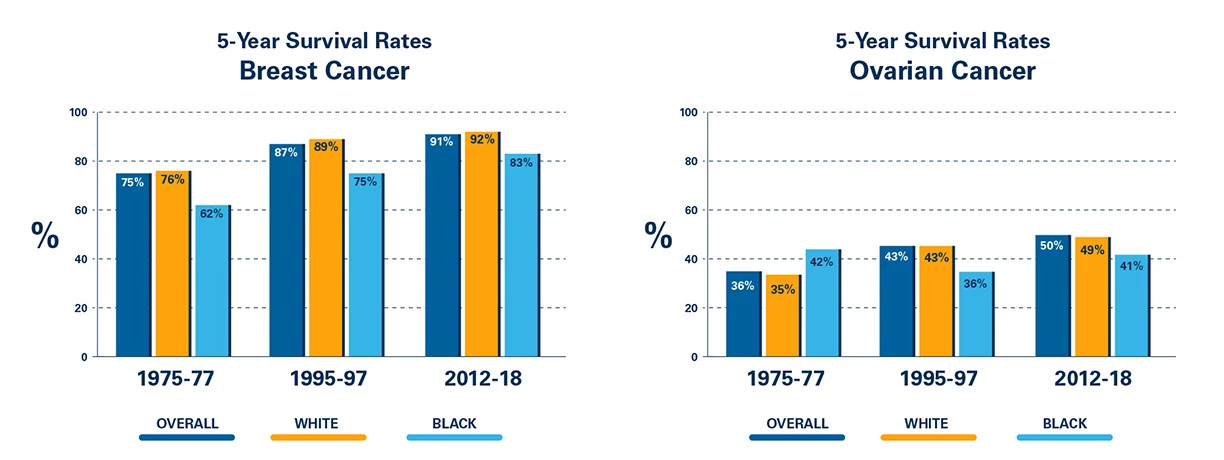

By many measures, progress has been impressive: a 21% overall improvement in breast cancer survival and a 39% improvement for ovarian cancer since the mid-1970s. But beneath these aggregate numbers are layers of data that reveal a more complex reality: Certain groups of patients continue to fare worse than others.

In breast cancer, for example, Black women and white women are diagnosed at roughly the same rate, but Black women are 40% more likely to die of the disease. The disparity is even greater for women under age 50, where the mortality rate for Black women is twice that of white women. In ovarian cancer, mortality for Black women is 1.3 times higher than for white women, even though the disease is more common in white women.

On a graph of breast and ovarian cancer survival rates, the lines representing Black women and white women rise roughly in tandem. But though their trajectories are similar, their endpoints are not: At any given point on the chart, the rate for white women is higher than that for Black women. The gap means that today, the survival rate for Black women with ovarian cancer is roughly what it was for white women in the mid-1990s.

Unlike breast and ovarian cancer, survival rates for cervical and uterine cancer haven’t risen much over the past 40 years. Here, too, however, disparities persist.

Breast and ovarian cancer survival rates rise roughly in tandem for Black and white women, but their endpoints are not the same: The survival rate for white women is significantly higher than that for Black women.

Other factors cut across racial lines. Lower socioeconomic status, lack of adequate health insurance or of facility with English, poor diet, physical inactivity, unhealthy living conditions, even geographical location are often associated with worse outcomes regardless of race or ethnicity.

The connections between racial, economic, behavioral, and environmental factors and decreased survival rates aren’t hard to trace. Patients with lower income may have more difficulty accessing the care they need. They may lack transportation to a treatment center or have difficulty affording their medications. Patients from traditionally underserved groups may feel apprehensive in a hospital or clinical environment because of an unfamiliarity with such facilities. Patients of different national origins may have difficulty navigating the American health care system, particularly if it is different from systems they've encountered elsewhere.

The overall rise in cancer survival rates has brought these disparities into higher relief — and given new impetus to efforts to reduce or eliminate them. Having achieved outstanding results for some patients, the cancer care community is facing up to its obligation to achieve them for all patients.

Tackling the Basics

At the Susan F. Smith Center for Women's Cancers, a variety of efforts are under way to reduce disparities. Many of these seek to remove some of the most fundamental obstacles patients face — difficulty in getting to and from appointments at Dana-Farber, and concerns about being feeling out-of-place or overwhelmed at the Institute.

In the gynecologic oncology program, Imani Holloman stands ready to help with these and other issues. As a patient navigator, she works with patients from the Boston neighborhoods of Dorchester, Jamaica Plain, Mattapan, and Roxbury, which have a lower socioeconomic profile than other parts of the city.

Many patients are looking for someone to listen to them. That's why I like to meet them for their first appointment, so we can form a connection. I want them to feel safe with me. The more I understand about what's happening in their lives, the better I can communicate that to their care team.

"I welcome all new patients from these priority neighborhoods," says Holloman, who joined the Institute in 2021. "I like to contact them before their initial appointment to welcome them to Dana-Farber. I also inform them about programs and services that offer emotional and financial support."

That can include arranging for transportation, meeting patients when they arrive at the Institute and walking with them to their appointments, arranging for an interpreter, and connecting them with social workers at the Institute and with outside organizations that can provide financial assistance if needed.

"Many patients are looking for someone to listen to them," Holloman remarks. "That's why I like to meet them for their first appointment, so we can form a connection. I want them to feel safe with me. The more I understand about what's happening in their lives, the better I can communicate that to their care team."

In the breast oncology program at Dana-Farber, researchers are exploring another way of learning about issues that may be making it difficult for patients to seek care or keep up with their treatment plan.

"Traditionally, clinicians might learn about problems patients are having at home or work by chance — by an offhand remark a patient makes," says Temidayo Fadelu, MD, MPH, who is participating in the research. "But we haven't had a systematic way of assessing some of these social determinants of patients' health."

A program called Lift Up is testing the feasibility of a more formal alternative to that chance-reliant approach. Research led by Rachel Freedman, MD, MPH, and Dr. Fadelu has resulted in a questionnaire for patients with metastatic breast cancer to complete when they arrive for their first appointment or early in the course of their care.

The questionnaire seeks basic information: Will a patient need an interpreter? Do they have transportation to the Institute? Can they afford insurance co-pays? Has their illness affected their ability to work or their family income? Do they have adequate housing? Are they feeling depressed or anxious?

The goal is to identify, early on, patients who have special needs, and to use that information to connect them to resources that can help address those needs. Three to six months after they complete the questionnaire, we're planning on surveying them to see whether the needs they identified were met.

"The goal is to identify, early on, patients who have special needs, and to use that information to connect them to resources that can help address those needs," Dr. Freedman says. "Three to six months after they complete the questionnaire, we're planning on surveying them to see whether the needs they identified were met."

Lift Up is being piloted among 200 patients as part of the EMBRACE (Ending Metastatic Breast Cancer for Everyone) program, which brings together doctors, nurses, social workers, and other clinicians at the Susan F. Smith Center to provide personalized treatment and support for patients whose breast cancer has spread beyond the breast.

"EMBRACE research coordinators reach out to patients to see if they'd like to participate in EMBRACE, and as part of that reaching out, are asked if they want to participate in Lift Up," Dr. Freedman says.

Equalizing Enrollment

Racial disparities in women's cancers are not limited to survival rates. They're also seen in clinical trials, where non-white patients have traditionally enrolled in significantly smaller percentages than white patients. Some of this resistance may trace to historical instances of mistreatment of Black patients and the distrust of the medical field it sewed in the African American community. The shortfall is concerning not only because it means fewer non-white women are receiving cutting-edge therapies but also because trials without diverse enrollment may have limited applicability.

"[In our breast oncology program, we've] made it a priority to do all that we can to improve accrual of diverse populations to our clinical trials," says Erica Mayer, MD, MPH, director of clinical research for breast cancer. "We know that patients benefit and the research itself will be stronger as a result of these changes."

To broaden the representation of different patient groups, investigators are opening trials that encompass not only Dana-Farber's Longwood Medical Area campus but its regional campuses across eastern Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire.

"We also have partnerships with cancer centers in parts of the country with diverse populations," Dr. Mayer remarks. "And within Boston, we're strengthening our partnership with Boston Medical Center, which serves a widely diverse community."

Clinical trial leaders are also working to make the logistics of trial participation easier for patients to manage.

"Being on a trial can be challenging and can involve a significant investment of time, energy, and financial resources" Dr. Mayer observes. "It may mean missing a day of work or traveling a substantial distance to get to the Institute. We're working with pharmaceutical companies, who sponsor many of our trials, to help patients defray these expenses, whether it's for transportation and parking or overnight lodging. We're also having trial consent forms translated into other languages to lower one of the barriers to trial participation for non-English-speaking patients."

The same spirit of inclusion resides at Dana-Farber's Center for Cancer Genetics and Prevention, which provides testing for inherited susceptibility to cancer and counseling on how to manage cancer risk. All patients with a cancer diagnosis are eligible for genetic testing, and the center has made it exceptionally easy to get tested.

With the Rapid Access Cancer Genetic Testing Program, patients can schedule a 30-minute visit with a genetic testing coordinator at the end of their first day at Dana-Farber.

"They watch a video, either in Spanish or English, that we've developed on testing for inherited cancer-risk genes, and afterwards they can ask questions and consent to testing and have their blood drawn the same day," says Huma Rana, MD, MPH, clinical director of Cancer Genetics and Prevention. "It may be difficult for people to make multiple trips to the Institute. This program opens genetic testing to a much broader group of people."

In a new study, Dr. Rana and her colleagues are working to adapt the video for patients from historically underserved populations. "We've interviewed 20 patients from these groups — half African American and half of Spanish language preference, from Dana-Farber and the Cancer Institute of New Jersey — and asked what they took away from the video, what they understood from it," Dr. Rana relates. "We're using their feedback to refine the video, and we'll test the revised version in a randomized trial. We're hoping to make it more useful for everyone."

Through efforts like these, researchers at the Susan F. Smith Center are working to ensure equal access to care and, ultimately, improved outcomes for all patients.